A worldwide shortage of sand

Tampa Florida. Pam Ferris-Olson

There’s something magical, transformational even, when feet released from the confines of socks plunge into a sun-warmed, talc soft beach. It’s a tonic for melting away the inconveniences of travel and the work-a-day world. In those moments, every grain of sand feels worth whatever it took to get to this beach front oasis.

Coastal refuges have long held the power to attract humans. In fact, according to UN-Habitat, half of the world’s population lives less than 100 miles or roughly 150 km from the coast, a figure that is “greater in number than that of people who inhabited the entire globe around 1950.” Concomitant with this growth is the need to build infrastructure and, thus, an increase in demand for concrete which is a significant driver of sand extraction and the environmental threats associated with that process. These include shore erosion, increased pollution, and a reduction in biodiversity. Associated with a decline in the coast’s ecologic and aesthetic values is an increase of economic hardships.

Sand as a resource

Sandy stretches of land reach out to meet the sea along most every coastline. When the vast expanses of inland deserts are included, it seems as though the world is awash with sand. Sand, however, is neither an unlimited resource nor is it created equally. Sand grains are classified by their physical and chemical characteristics and its source of origin (e.g., river, lake, or marine). Desert sand grains are smoothed and rounded by the wind over millennia. Desert sand is functionally useless for the production of concrete, the major consumer of sand. Sand that has been scoured by water and made jagged and angular, however, is highly desirable. This type of sand is needed for construction, mined for minerals, and transported to beaches to reclaim what has been eroded by wave action.

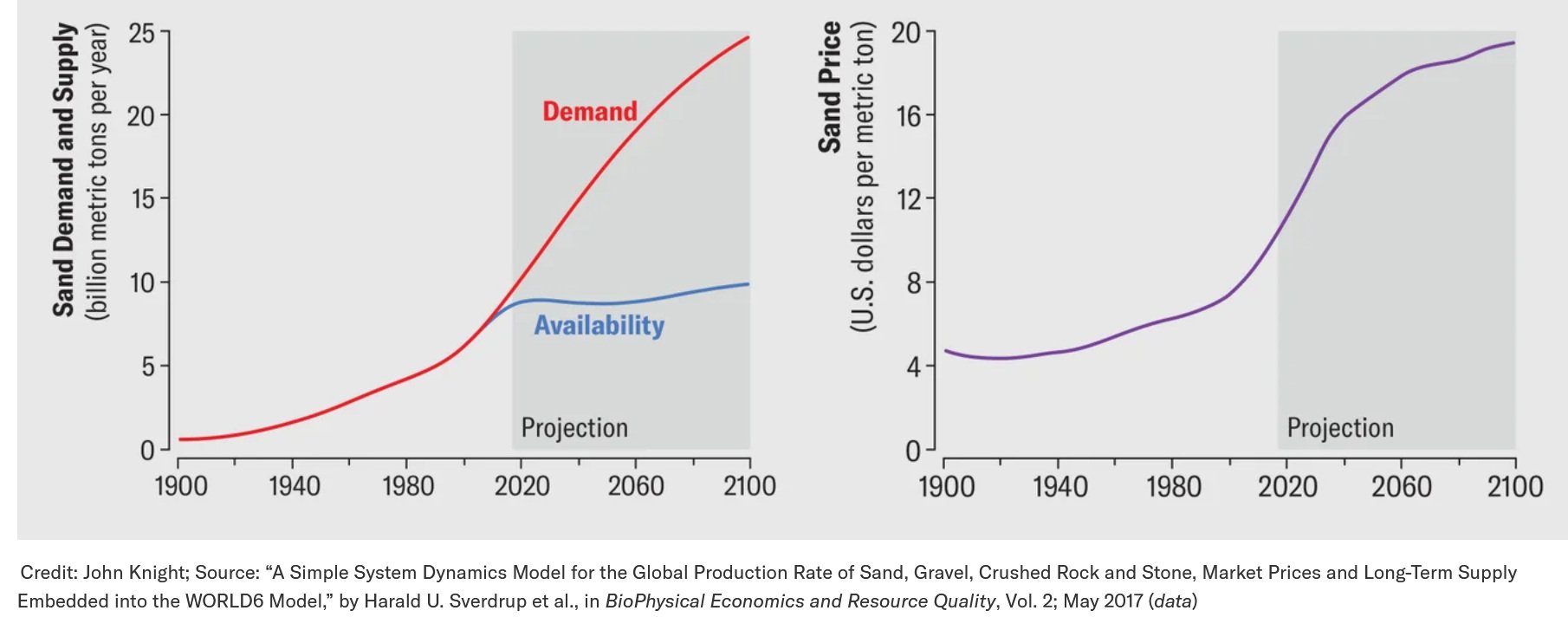

In addition to concrete production, coastal sand is used in the manufacture of glass, electronics, asphalt, and in processes such as fracking and land reclamation. Coastal sand extraction is estimated at 44-55 billion tons (40-50 billion metric tons) annually with 85 percent going toward construction. Demand for coastal sand is so great that it has become “the most used natural resource in the world after water.” The rate of extraction now exceeds the natural rate of replenishment. According to Vince Beiser, author of The World in a Grain, China is the primary user. China he wrote “used more cement in three years (6.6 gigatons from 2011 through 2013) than the U.S. used in the entire 20th century (4.5 gigatons).” A 2022 study by researchers at the University of Amsterdam estimated that the world could run out of construction-grade sand by 2050.

Sand mining has been implicated in a range of adverse environmental impacts such as the deterioration of air and water quality, reduction in biodiversity, and the ability of mined areas to buffer against storm surge and sea level rise. Sand mining also negatively impacts local economies and social conditions. As the land is altered employment opportunities are likely to decline as is the availability of locally sourced food and the well-being of the local population.

In addition to its utility to the construction industry, sand is sought after for its mineral composition and perceived benefits in beach nourishment projects. Minerals commonly extracted from sand include are precious metals like gold and a host of lesser known minerals important in the production of such things as cell phones and cars. These valued minerals make up less than 10 percent of the total volume of mined sand, the remaining 90 percent is typically treated as a waste product. When viewed as a waste product, the remaining sand is disposed of in a manner that further compounds the environmental damage of the mining process.

Sand for beach restoration - The case of Oak Island

International news was buzzing in 2008 with the story of a large scale sand heist in Jamaica. Hundreds of tons of white sand, an estimated 500 truckloads, were removed from Coral Spring Beach. The local authorities never recovered the stolen sand. It was suspected the sand had been sold to replenish the sand of a rival resort. Such a story seems out of the ordinary, a made for television events; however, sand theft is not the stuff of fiction. The fact is that sand mining, whether destined for beach restoration or the construction industry and whether illegally or legitimately obtained, it occurs everywhere from Morocco to Brazil and the United States to China. One federal police specialist who specializes in extractive industries, estimated that “the global illegal sand trade ranges from $200 billion to $350 billion a year—more than illegal logging, gold mining and fishing combined.”

Although sand heists make good stories they have horrible consequences for the local communities where the sand is removed. A different type of story involves communities that are seeking sand as they struggle to ward off the ravages of Mother Nature. One such place is Oak Island, a beach town at the southern end of North Carolina’s coast. Every summer Oak Island’s beaches attract tourists in numbers that cause the population to grow by nearly 500 percent, from a few thousand to nearly 50,000.

Gareth McGrath, the climate change/environmental reporter for the local StarNews, reported that Oak Island began its beach nourishment program in 2001. The program was seen as a way to repair the damage caused two years earlier by Hurricane Floyd. Since then Oak Island has grown increasingly dependent on sand-pumping projects to maintain its beaches and protect its tourist economy and oceanfront properties. Beach nourishment projects also have been carried out in 2009, 2015, and 2022. The cost of these restoration projects is largely funded by local taxpayers. The price tag has been growing, a frustrating situation because pumping is only a temporary solution. The expected cost for a 2024 project is estimated at $40 million but is a small fraction of the cost of a proposed 50-year nourishment project that would pump sand from a shoal 25 miles offshore.

Oak Island is one among nearly every North Carolina beach town that is fighting erosive forces to their beaches. This makes them all competitors in the search for sand to replenish their shrinking beaches. This demand far outstrips the sand that has traditionally come from dredging shipping channels. As a result the communities are looking farther offshore to procure sand and building artificial structures to hold off the erosive forces of the oceans. Terminal groins, for example, are costly hardened structures. They protect some of the beach but cause unintended erosion in adjacent areas as well as degrading the surrounding habitat.

The situation at Oak Island and its sister beach communities in North Carolina is not unique. Beach depletion is occurring from Maine to San Diego. The approach to mitigating beach erosion differs with some communities acknowledging that the costs of fighting the beach loss is too high. Residents reluctantly retreat inland away from the shore. Others are determined to stay put and fight. They seek new sources of sand and build retainment structures even though the costs are increasingly burdensome. Still others are using nature herself, replenishing sea grasses and reconstructing coral reefs, to reduce the erosive force of wind and waves.

As a sustainable resource?

Are there sustainable solutions to the worldwide demand for sand? The United Nations Environmental Programme proposed national standards be set for every country, standards based on a country’s specific circumstances. These standards focus on local issues but remain mindful that there are “downstream” ecosystems that deserve protections. Such protections should include buffer zones for sensitive habitats, investment in technologies that reduce sand consumption, and consistent and enforceable strategies that target the illegal sand trade.

Individuals can be part of the solution. Individuals have agency to make choices. Look for websites that identify construction materials that are sustainably sourced and ready product labels to determine the source of their materials.

Although other practices may not target sand, everyone can make a more conscious effort to engage in sustainable practices. For example, when selecting a hotel or resort as about their recycling policy. Do they have a plan to save water? Do they purchase goods locally? Check out travel sites like Lonely Planet to locate sustainable hotels. Let hotel managers know that you appreciate their efforts. Let them know when a practice makes you uncomfortable. Suggest how they might make a change for the better.

Everyone can make a more conscious effort to recycle, purchase locally, and select sustainable products. Avoid fast fashion and production practices that result in high levels of waste or involve high plastic content.

Working together we can make a difference. Stay informed and learn how you can take action.